Rotary Switch Engineering Information

- Jul 23, 2021

- 10 min read

Catalog Ratings

Are catalog ratings misleading? In most cases, yes. Load and life ratings shown in most catalogs are usually invalid for most applications. This results from the complex interplay of such factors as environment, duty cycle, life limiting or failure

criteria, actual load, etc. Circuit designers should be aware of these factors, and the effect they have on the useful life of the switch in their applications.

The problem of switch rating arises from the wide variety of requirements placed on the switch. This includes various applications, and the sensitivity of the switch to a change in requirements. If we attempted to establish life ratings for all possible applications, we would have an almost infinite variety of ratings.

To simplify the problem, switch manufacturers, switch users, and the military, have established certain references for ratings. These include loads, life requirements, environments, duty cycles, and failure criteria. These references are arbitrarily established. But, they allow you to compare different switch designs. They do not,

however, match the actual requirements for most applications.

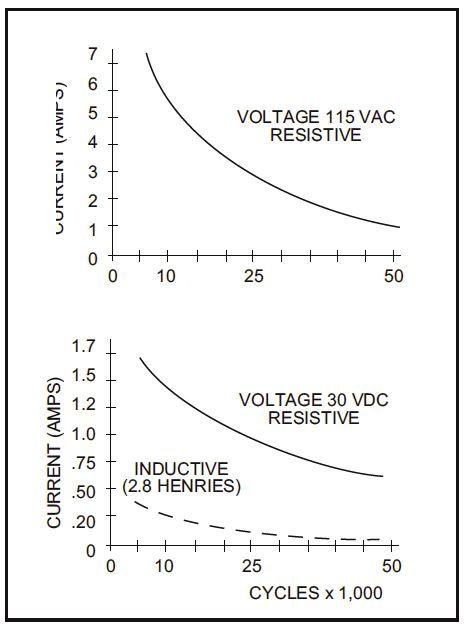

The curves shown here are an example of some of the life load curves. These curves are life load characteristics of the Grayhill 42M and 44M switches. Note that the curves consider only two voltage sources and two types of loads. These voltages and loads are, however, considered as standards for testing procedures by the industry.

Curve data is based on tests conducted at sea level, 25°C and 68% relative humidity.

Cycle = 360° rotation and return. Cycling rate is 10 cycles per minute. Switch rating is for

non-shorting contacts.

These curves allow you to predict the expected life of the switch once you know the voltage, current and type of load. Also note that each cycle is approximately a 360° rotation and a return. For a ten position switch this would be a rotation from position 1 to position 10 and back to 1. This cycle runs approximately ten times a minute. Thus testing causes more electrical and mechanical wear than what the switch incurs in actual use.

Summary

The life and load ratings in this and other catalogs are probably not totally valid for your application. The bright side of the picture is that in most applications the switch will perform better than its ratings. This is because the standard industry test conditions are more stringent than those found in most applications.

This difference can be very dramatic. For example, Grayhill’s 42A and 44A Series Rotary Switches, are rated at 1 ampere (115 Vac resistive). However, they will operate at 5 amperes in many applications. To see how some major factors influence switch performance, read on.

USEFUL LIFE CRITERIA

The “useful” life of a switch in your application depends on what you demand of it. This includes parameters such as contact resistance, insulation resistance, torque, detent feel, dielectric strength, and many other factors. For example, a contact resistance of 50 milliohms may be totally unusable in certain applications such as a range switch in a

micro-ohm meter. In other applications a contact resistance of 5 ohms may be perfectly satisfactory.

In establishing “useful” life for a switch in your application, you must first determine “failure criteria,” or “end of life” parameters. At what level of contact resistance, dielectric strength, etc., is the switch no longer acceptable for your application?

Most switches are acceptable on all parameters when new. There is a gradual deterioration in performance with life. The rate of deterioration varies greatly with basic switch design. Often, circuit designers select a switch on the basis of its performance when new. This is a mistake. The performance of the switch after several years of equipment use is more significant. To estimate this, first determine the life limiting or

failure criteria for your application. In most uses, important life-limiting (failure) criteria include the following parameters:

Contact Resistance

Insulation Resistance

Dielectric Strength

Actuating Force

Contact Resistance

This is the resistance of a pair of closed contacts. This resistance effectively appears in series with the load. Typical values are in the range of a few milliohms for new switches. These values usually increase during life. The rate of increase is greatly affected by the voltage, current, power factor, frequency, and environment of the load being switched. Typical industry standard “end of life” criteria for this parameter are:

MIL-DTL-3786: 20 milliohms (Rotary Switches)

MIL-S-6807: 20 milliohms (Snap Pushbuttons)

MIL-S-8805: 40 milliohms (Pushbuttons)

MIL-S-83504: 100 milliohms (DIP Switches)

Contact resistance can be measured by a number of different methods. All of them are valid depending upon the switch application and the circuit. Grayhill uses the method in applicable military specifications. This method specifies an open circuit test voltage and a test current. The voltage drop across the closed contacts is measured. The contact resistance is determined by Ohm’s Law from the test current and the measure voltage

drop. MIL-DTL-3786, MIL-S-6807 and MIL-S-8805 require a maximum open circuit test voltage of 2 Vdc; they require a test current of 100 milliamperes. MIL-S-83504 requires a maximum test voltage of 50 millivolts and a test current of 10 milliamperes.

When a switch is rated to make and break 5 or more amperes, there is a difference. Contact resistance is determined by measuring the voltage drop while the switch is carrying the maximum rated current. The voltage drop that occurs across the contacts

determines, in part, the contact temperature. If the temperature rise of the contacts is sufficient, it affects contact material. A chemical reaction will take place that can cause an insulating film to appear on the contacts. This film is present between the contacts during the next switching operation. This film formation can cause failure due to increasing contact resistance. For switching of very low voltages and currents, this resistance may be the failure criteria.

Insulation Resistance

This is the resistance between two normally insulated metal parts, such as a pair of terminals. It is measured at a specific high DC potential, usually 100 Vdc or 500 Vdc. Typical values for new switches are in the range of thousands of megohms. These values usually decrease during switch life. This is a result of build-up of surface contaminants. Typical industry standard “end of life” criteria for the parameter are:

MIL-DTL-3786: 1000 megohms (for plastic insulation)

MIL-S-6807: Not specified

MIL-S-8805: 2000 megohms

MIL-S-83504: 1000 megohms

Dielectric Strength

This is the ability of the insulation to withstand high voltage without breaking down. Typical values for new switches in this test are in excess of 1500 Vac RMS. During switch life, contaminants and wear products deposit on the surface of the insulation. This tends to reduce the dielectric withstanding voltage. In testing for this condition, a voltage considerably above rated voltage is applied. Then, the leakage current is measured at the end of life. Typical industry standard test voltages and maximum allowable leakage currents are as follows:

MIL-DTL-3786: 1000 Vac and 1 mA maximum leakage

MIL-S-6807: 600 Vac RMS after life and 10 microamperes maximum leakage

MIL-S-8805: 1000 or 1000 plus twice working voltage (AC) RMS and 1mA maximum leakage

MIL-S-83504: 500 Vac and 1 mA maximum leakage

UL Standard: 900 Vac without breakdown (UL Standard (dependent on test)

Voltage breakdown is another method for describing the ability of the insulating material to withstand a high voltage. Voltage breakdown describes the point at which an arc is struck and maintained across the insulating surface with the voltage applied between the conducting members.

ADDITIONAL LIFE FACTORS

Effect of Loads

On any switch, an arc is drawn while breaking a circuit. This causes electrical erosion of the contacts. This erosion normally increases contact resistance and generates wear products. These wear products contaminate insulating surfaces. This reduces dielectric strength and insulation resistance.

The amount of this erosion is a function of current,

voltage, power factor, frequency and speed of operation. The higher the current is, the hotter the arc and the greater the erosion. The higher the voltage is, the longer the arc duration and the greater the erosion.

Inductance acts as an energy storage device. This returns its energy to the circuit when the circuit is broken. The amount of erosion in an inductive circuit is proportionate to the amount of inductance. Industry standard test inductance as described in

MIL-I-81023 is 140 millihenries. Other test loads include 250 millihenries and 2.8 henries.

Frequency can also affect erosion. The arcing ends when the voltage passes through zero. To a certain extent, the following is true. The higher the frequency, the sooner arcing ends, the lower the erosion.

The speed of operation affects the duration of the arc. Fast operation can extinguish the arc sooner. This reduces the erosion, unless the air within the switch is completely ionized.

Actuating Force

Rotational torque is the actuating force required to turn a rotary switch through the various positions. The actual torque or force required depends on the design of the switch. It varies widely from one design to another. See appropriate MIL Specs or

manufacturers literature for typical industry values for specific designs.

When torque or force values are specified, it is customary to give a minimum and maximum value. During life, two offsetting factors may occur to change the initial value. Relaxation of spring members will tend to lower torque or force values. Wear or “galling” of mating surfaces, however, may tend to increase these values. Typical end of life specifications may require the switch to fall within the original range. Or, they may specify a maximum percentage change from original value. For example, “the rotational torque shall not change more than 50% from its initial value.

Effect of Ambient Temperature

Temperature extremes may affect switch performance and life. Very high temperatures

may reduce the viscosity of lubricants. This allows them to flow out of bearing areas. This can hasten mechanical wear of shafts, detents, plungers, and cause early mechanical failure. Contact lubricants are sometimes used. Too little lubrication can

result in a high rate of mechanical wear. Too much lubrication flowing from other bearing areas can adversely affect dielectric strength and insulation resistance.

Through careful design and selection of lubricants most manufacturers attempt to minimize these affects. Nevertheless, continual operation in high ambient temperatures will shorten the life of a switch regardless of design.

Extremely low ambient temperatures may also create problems. Low temperatures may cause an increase in the viscosity of the contact lubricant. Higher viscosity can delay or prevent the closing of contacts, causing high operating contact resistance. Under certain atmospheric conditions, ice may form on the contact surfaces. This also causes high and erratic contact resistance.

Neither of these conditions may materially reduce the life of the switch. However, it may

cause unsatisfactory operation. If the voltage of the circuit is high enough, it can break down the insulating layer. Some current will flow through the high resistance contacts. A local heating action is created, which tends to correct the condition in a short period of time.

Switches with high contact pressures may minimize the low ambient temperature effect. This is particularly true if the application calls for switching signal level voltages and currents.

Effects of Altitude

In high altitudes, barometric pressure is lower. Low pressure reduces the dielectric strength of the air. The arc strikes at a lower voltage and remains longer. This increases contact erosion. Switches for use in high altitudes will therefore require derating in terms of loads and/or life.

Effects of Duty Cycle

Mechanical life testers cause accelerated life testing. Testers operate switches at a rate of approximately 10 cycles per minute. This rate is greatly in excess of normal manual operation in equipment. It constitutes a severe test of the switch.

Lubricants do not have an opportunity to redistribute themselves over the bearing surfaces at this duty cycle. The contact heating caused by arcing does not have a chance to dissipate.

Thus, the switch runs “hot”, increased mechanical wear and contact erosion result. Your application probably requires manual operation of the switch with an attendant low duty cycle. If so, you can usually expect much longer switch life than is shown by the accelerated life laboratory life tests.

Conclusion

Remember, load and life ratings are based on manufacturers’ selected references. They

include accelerated life tests and an arbitrary set of application parameters and failure criteria. These parameters and criteria may not always fit your application.

Then how do you know if a switch will give reliable performance in your application?

How do you know if it will last the life of your equipment?

Ask the switch manufacturer. Grayhill, and most other reputable manufacturers have compiled vast quantities of test data. We are in a position to give a good estimate of a switch’s performance in many nonstandard applications. You should provide the following data:

Expected Life: in number of cycles

Load: voltage, current, power factor, and frequency

Operation: manual or mechanical, duty cycle

Application: type of equipment

Environment: altitude, ambient temperature range relative humidity, corrosive atmosphere, shock, vibration, etc.

Failure Criteria: end of life contact resistance, dielectric strength, insulation resistance, etc.

With this information, we can usually estimate if a given switch is suitable for your application.

Soldering

What causes failure in a new switch after it has been installed? The principle failure is high contact resistance caused by solder flux on the contact surfaces. To avoid this, be sure to follow good soldering practices. Use the proper solder with the proper flux core, maintain the proper soldering temperature, use the proper soldering iron tip for the work, and never use liquid flux when soldering a switch.

Do not use solvent baths or washes with any unsealed electromechanical parts. Switches, unless they have been especially protected suffer badly. Solvents readily dissolve fluxes and carry them into the contact area of switches. A thin, hard flux coats the contact surface after the solvent evaporates. Additionally, solvents may dissolve

and wash away lubricants in switches. Lubricant loss may prevent proper mechanical action.

Exercise similar precautions when you mount a switch to a printed circuit board. Maintain proper solder temperatures and follow proper cleaning techniques. Avoid subjecting these switches to lengthy solder baths. The excessive heat can deform the plastics.

RFI/EMI Shielding

Some applications require shielding against Radio Frequency Interference and/or Electro-Magnetic Interference. Experts feel that the most effective way to achieve shielding is to provide a conductive bridge across the component mounting hole.

They also generally agree that there is no good method for testing shielding. So, the equipment manufacturers themselves must identify and solve specific problems. Component manufacturers can generally assist in the solution of shielding problems.

RFI/EMI testing is incorporated into MILDTL-3786 for rotary switches. Requirements

are 1.0 ohm maximum dc resistance between the mounting bushing and operating shaft initially and 10.0 ohm maximum dc resistance following environmental and mechanical tests.

Many equipment manufacturers feel they are satisfying their needs with a measurement of .025 to 10 ohms for the expected life of the switch. Under most circumstances, standard non-sealed switches pass the larger value easily. The lower

value (.025 ohms) requires special attention and parts for compliance over the life of the switch.

Switch Selection

Whenever possible, use standard switches and contact configurations. Standards provide the greatest economy and the best delivery. When you need a deviation, it pays to consult with your suppliers as soon as possible. At the early stages of the design, there are many low cost options for achieving the results. At the late stages of design, some of the options may no longer be open. For example, size may be restricted. This

might result in a more costly redesign.

Typical standard rotary options are as follows: coded contacts, homing rotor effect, progressively shorting contacts, PC mountable terminals, rotary switch spring return positions, and push-to-turn or pull-to-turn mechanisms.

Limited panel space may be solved by a concentric shaft rotary switch. It is two rotary switches, located one behind the other. There are other concentric shaft possibilities. A rotary switch can be combined with another component. These include a potentiometer, a pushbutton switch, and a mechanical element. The most cost effective

design may be one of these concentric options. But, selection must be made at the outset of equipment design.

Comments